YA Pride: Interview with Madeleine George

In 2010 at the YALSA Literature Symposium, I heard Madeleine George reading from a work in progress. That reading was so funny and sharp that I couldn't wait to read the book that it came from. The only problem? That book, The Difference Between You and Me, wasn't due to be published until 2012. It was definitely worth the wait!

In The Difference Between You and Me, Madeleine tells the story of two girls at one high school. Jesse wears big green fisherman's boots and cuts her own hair with a Swiss Army knife. Emily is the student council vice president and wears sweater sets — plus she has a boyfriend. You wouldn't think Emily and Jesse have anything in common, but they do: They're having a secret relationship that involves making out in the library bathroom once a week. That's just the beginning, though. The book also tackles politics, capitalism, and protests while delivering some zingy dialogue that I'm convinced has been honed through Madeline's other job as a playwright.

In 2010 at the YALSA Literature Symposium, I heard Madeleine George reading from a work in progress. That reading was so funny and sharp that I couldn't wait to read the book that it came from. The only problem? That book, The Difference Between You and Me, wasn't due to be published until 2012. It was definitely worth the wait!

In The Difference Between You and Me, Madeleine tells the story of two girls at one high school. Jesse wears big green fisherman's boots and cuts her own hair with a Swiss Army knife. Emily is the student council vice president and wears sweater sets — plus she has a boyfriend. You wouldn't think Emily and Jesse have anything in common, but they do: They're having a secret relationship that involves making out in the library bathroom once a week. That's just the beginning, though. The book also tackles politics, capitalism, and protests while delivering some zingy dialogue that I'm convinced has been honed through Madeline's other job as a playwright.

She is a founding member of the Obie-winning playwrights' collective 13P, and is now a resident playwright at New Dramatists. Madeleine's plays, which have been performed across the United States, include The Zero Hour and Seven Homeless Mammoths Wander New England. I invited her to talk about The Difference Between You and Me, the difference between writing young adult novels (her first was Looks, published in 2008) and plays, and what's coming next.

Malinda Lo: One of the questions I get all the time, because I've written novels about lesbian main characters, is whether I faced any homophobia when trying to get published. Your first novel, Looks, wasn't about an LGBT character, but your second novel is. What was your publication process like for The Difference Between You and Me? Did you face any homophobic pushback during this process?

Madeleine George: I had no homophobic pushback whatsoever from my editor or publisher on The Difference Between You and Me, which was a great relief since I had such a terrible time getting to the story in the first place.

Madeleine George: I had no homophobic pushback whatsoever from my editor or publisher on The Difference Between You and Me, which was a great relief since I had such a terrible time getting to the story in the first place.

When I started my second book, I knew I wanted to write about heroism and the price of standing up for what you believe in, and I came up with this story about a girl in a small town who's obsessed with basketball and who ends up taking her school to court on a Title IX violation and becoming the town pariah (Title IX is the law that says schools have to treat boys and girls equally in all educational activities, including athletics). I came up with the story all at once and all of a sudden—while waiting at a red light at an intersection, actually—and I felt totally confident that this was going to make a brilliant, compelling book. I wrote a treatment for it, synopsizing every chapter, and submitted it to my editor, who blessed it and told me to start writing. So I dove into research and writing, and immediately I encountered two big problems.

The first was that I learned that, since the 1970s when it became law, Title IX has totally worked. All across the country, in small towns and big cities, girls play sports now and people are pretty chill about it. Of course there are still pockets of gender discrimination in athletics and education, and girls' games don't always draw the same crowds as boys' games, but it's the rare town that gets torn apart over funding for girls' athletics these days. This is a triumph for feminism, but it sucked for my novel, since that was supposed to be the main conflict of the story.

The second problem I encountered was closely related to the first: I didn't have the first clue about basketball, or anything to do with sports or athletics. I'm an anti-athlete, a jock-repeller, the kind of person who spent four years of high school making up increasingly desperate and far-fetched excuses to get out of gym class ("I couldn't get to my sneakers because we had our floors stained and my sneakers were on the other side of the room with the wet floor," I actually told my 10th-grade P.E. teacher, who wearily waved me away towards the bleachers).

As a writer, I wasn’t about to let my appalling ignorance stop me; I'm very much of the write-what-you-want-to-know, not the write-what-you-know, school of thought. But as many girls' basketball games as I attended, as many youtube videos as I watched, as many coaching manuals as I read to try to understand the game, I had an extremely difficult time getting inside the mind and body of a skilled player. I even made my patient friend Gary meet me at the gym to try to teach me how to handle a basketball (does it seem incredible that I had basically never touched a basketball when I decided to write this book? But I hadn't). I could barely keep the ball in my hands while I was standing still, let alone "dribble" it down the court and "shoot" it through the mounted string bag that is apparently the holy grail of this game.

So as ardent as I was about my story's basic shape, I was doing a very bad job actually writing it. I slogged through about sixty elementally awkward, unconvincing pages before my editor called me in and told me that I was barking up the wrong tree and had to start again from scratch. I went into temporary free-fall, mourning the idea I had become attached to during a year's worth of work and feeling aimless and depressed about the project of writing novels in general.

But my friend Carley Moore, a brilliant poet and YA novelist and one of the sanest sources of writing advice I know, walked me through the process of returning to my original impulses. Basketball had just been the vehicle for me to write about my real topic: heroism, and the sacrifices people make in order to lead a principled life. So I broke my bad story down to its basic elements and put them back together in a new form, with new characters whose personalities, habits, and motivations were just a little bit closer to my own, and which I could therefore render with a more truthful, vivid hand. I may not know a layup from a layover, but I know all too well what it's like to get spun around by a girl you can't help craving even though she's guaranteed to break your heart. And my editor didn't bat an eye when I pitched the new story, which had the protagonist falling for another girl instead of for a team sport.

That's a long answer, and it's all about writing process, not about struggling to overcome homophobia at all. I guess that's a nice comment on the political climate of YA publishing right now!

ML: One thing I love about Jesse, one of the girls in The Difference Between You and Me, is that she's not traditionally feminine. In YA, you don't find too many girls like her. Have you heard from readers about how they feel about Jesse? How do they react to her?

MG: A number of young readers have told me that they like reading about an openly lesbian teenage character, but I find that they're more focused on what Jesse does in the book than what she looks like. They tell me that they admire Jesse or are frustrated by her—kids who are out have often told me how angry they are with Jesse for liking someone who persuades her to stay in the closet, which I totally appreciate. But I haven't had one young reader talk to me specifically about the fact that Jesse is butch.

Maybe this is because you have to be pretty brave to talk about butchness when you're a teenager—I know I didn't have any vocabulary to talk about gender presentation when I was a kid, only the vague, inchoate sense that I wasn't properly a girl and couldn't pull off the clothes, gestures, and behaviors that made other girls "normal." Adult readers have mentioned that they liked reading about the bathroom problem in a YA novel (Jesse gets gender-checked in the girls' room, a pretty common experience for masculine girls and women), but I've never had a young reader discuss the gender identity of my protagonist with me.

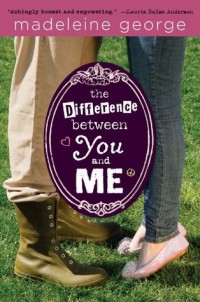

Here's one interesting thing about gender that came up during the publishing process, though. The cover of the ARC of The Difference Between You and Me was very pink and purple and sweet, designed around a photograph of two pairs of feet facing each other, one in ballet flats and the other in big green boots, like the ones Jesse is described as wearing in the book. The image was super cute but somehow coy—without the rest of the bodies in the photograph, the picture couldn't be read for gender, and instead of seeming gender-neutral it ultimately made the cover feel like a bait-and-switch: I had one reader tell me that she assumed at first glance that the book was a romantic comedy between a girl and an outdoorsy boy, and was stunned when she opened it and found an anti-corporate lesbian love story inside.

Here's one interesting thing about gender that came up during the publishing process, though. The cover of the ARC of The Difference Between You and Me was very pink and purple and sweet, designed around a photograph of two pairs of feet facing each other, one in ballet flats and the other in big green boots, like the ones Jesse is described as wearing in the book. The image was super cute but somehow coy—without the rest of the bodies in the photograph, the picture couldn't be read for gender, and instead of seeming gender-neutral it ultimately made the cover feel like a bait-and-switch: I had one reader tell me that she assumed at first glance that the book was a romantic comedy between a girl and an outdoorsy boy, and was stunned when she opened it and found an anti-corporate lesbian love story inside.

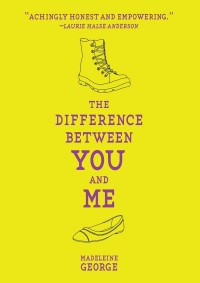

When the book went to print, the cover was changed to a much bolder, graphic image of a single boot over a single ballet flat, and that iconic image of two different shoes is much sexier and more obviously queer to me than the photographic cover ever was. It telegraphs something important about the mystery, fluidity, and dynamism of gender, and it also plays up the meaning of the title—the differences between Jesse and Emily may ultimately be the downfall of their relationship, but they're also what draws them together in the first place: Jesse loves Emily's hyperfeminity, and though she can't admit it to herself, Emily loves the boyishness of Jesse, more than she loves the boyishness of her actual boyfriend.

ML: I have to ask a nerdy writer question. Why did you choose to write Emily and Esther's chapters in first person, but Jesse's in third person?

MG: I did this very deliberately, though from what I hear from readers it's the most controversial aspect of the book—way more incendiary than the girl-on-girl love scenes.

I know a lot of people believe that first person is the closest, most intimate mode of narrative, the one that reveals the deepest truth about a character. But as a playwright, I have a different perspective. In a play, every character speaks in the first person, but the audience sees that each character's perspective is necessarily limited—the world of the play is much bigger than any one individual, and each character can only see her own narrow sliver of what's around her.

As a playwright, whenever I hear a character launch into a first-person monologue about who they think they are, what they believe, etc., I automatically hear it with skepticism, knowing that the play itself—if it's any good—will ultimately reveal the holes in that character's claims. So for me, first person has always been the most narrow mode of narrative, often deluded and self-serving, or at the very least isolated from the world.

I gave the deluded first person to Emily, the character who's least in touch with her own motivations and most involved in fabricating elaborate self-justifications to allow herself to continue to act hypocritically. And I gave the third person to Jesse, the character who's more integrated and aware of who she is, because I wanted to give her version of the story more cred and legitimacy. Even when Jesse is making a conscious decision to lie about her relationship, she always knows the truth, and I wanted her chapters to feel like they were taking place in the real world, while Emily's chapters take place inside her own fevered mind.

ML: Do you consider your plays to be for adults? How do you feel writing plays differs from writing young adult novels?

MG: I do think of my plays as for adults, though only because they're about adults—there's nothing in them that teenagers couldn't see. Plays vs. novels is an interesting question. There are lots of distinctions between the forms, of course, but at heart I think playwrights have a different relationship to time than novelists do (and poets, and screenwriters, and short story writers—often think of the different genres of writing as differing mainly in terms of time signature).

Characters in plays live very breathless, moment-to-moment lives—we follow them in real time as they experience unexpected events, get knocked for a loop, transform, start again. In novels, we can be told a story in retrospect, and the sense of time is much more expansive and elastic. Some moments blow up big and vast and significant, other moments are edited out of the chronology completely.

I guess I'm a naturally breathless, real-time storyteller, and I've been allowing myself to write pretty theatrical novels—in the present-tense, for example, with shifting perspectives from chapter to chapter. So in my third book I'm setting myself the challenge of trying to write more like a fiction writer—expanding and compressing time to suit my story—and less like a playwright, stuck on the idea of real-time scenes. We'll see how it turns out!

ML: Do you have another YA novel waiting in the wings?

MG: I'm so early in the process of working on my third YA novel that I can't say much definitively about it. I'm sure there will be queerness in it, in some form or other, and romance, and probably the struggle to become independent from your parents. There might also be questions about God, and what it means to be a spiritual kid in a family of atheists. Mostly I'm spending my time right now reading everything ever written by Nick Hornby, whose generous, witty style and crisp plotting I hope to slavishly imitate in book three. It's a pretty fun way to "research" a book.

Thanks, Malinda, for inviting me to visit, and for asking me such interesting questions!

ML: You're welcome!

>>>

As part of my YA Pride celebration, I'm giving away a copy of Madeleine George's The Difference Between You and Me to one lucky winner!

The fine print:

- To enter, simply enter your email address in the Rafflecopter widget below so that I can contact you if you win.

- The winner must be able to provide a valid United States mailing address where he/she can receive the prize.

- The deadline for The Difference Between You and Me giveaway is July 3, 2012!

- Winners will be notified by email, and prizes will be mailed in July 2012.