E.M. Kokie Interviews Sara Farizan

By E.M. Kokie

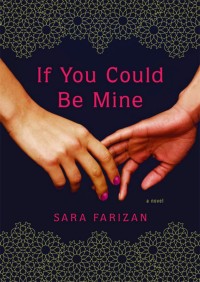

Sara Farizan’s debut YA novel If You Could Be Mine (Algonquin, August 2013), deftly explores the cross-section of gender, gender identity, and sexual identity for a lesbian teen in modern Iran.

Sara Farizan’s debut YA novel If You Could Be Mine (Algonquin, August 2013), deftly explores the cross-section of gender, gender identity, and sexual identity for a lesbian teen in modern Iran.

Seventeen-year-old Sahar is in love with her best friend Nasrin. Nasrin loves her in return, and the two share stolen kisses and a growing heated attraction. But they live in Iran, where homosexuality is punishable by death. As Nasrin’s arranged marriage to a man approaches, Sahar is desperate to find a way to stop the wedding so they can be together. Their frantic fear at being parted causes them both to take risks. Then Sahar, through her cousin Ali, finds a possible solution. In Iran, it may be a sin to be homosexual, but it is not a sin to be transgender. Sahar stumbles blindly after what she views as the obvious solution, but is forced to examine who she really is, and how much of her person is her sexual identity, her gender identity, and her identity as a daughter and a woman in Iran.

While reading If Your Could Be Mine, I was struck by how many different ways it could mirror the varied experience of LGBTQ people, and how many windows it could open for readers to experience the lives of those so different from themselves. Further, I was fascinated by its exploration of the disparate view and treatment of homosexual and transsexual people in Iran. (My full review is here).

School Library Journal said, “Rich with details of life in contemporary Iran, this is a GLBTQ story that we haven’t seen before in YA fiction. Highly recommended.” And a starred review from Booklist called If You Could Be Mine an “accomplished and compassionate look at a heartbreaking situation” and praised its “groundbreaking, powerful depiction of gay and transsexual life in Iran and its similarities to and differences from that of the West.”

School Library Journal said, “Rich with details of life in contemporary Iran, this is a GLBTQ story that we haven’t seen before in YA fiction. Highly recommended.” And a starred review from Booklist called If You Could Be Mine an “accomplished and compassionate look at a heartbreaking situation” and praised its “groundbreaking, powerful depiction of gay and transsexual life in Iran and its similarities to and differences from that of the West.”

I was thrilled to have the opportunity to interview Sara and ask her some of my burning questions about her characters, their world, and Sara’s own experiences.

E. M. Kokie: What inspired you to write If You Could Be Mine?

Sara Farizan: I had a very difficult time as a teenager coming to terms with my sexuality and understanding that I was gay. A lot of that difficulty stemmed from my cultural background. My parents are originally from Iran, and thankfully they love me unconditionally, but I worried a lot about disappointing them or having them be embarrassed among the Persian community here. It was a really challenging time reconciling these two identities and I finally figured out that there wasn’t anything wrong with me. Unfortunately as a teenager when I was reading books that could speak to my experience, there wasn’t anything about a young person of Eastern background who was also dealing with their sexual orientation.

I was writing a lot about these issues for my own sake and writing for my inner teenager. I was writing Persian American characters, but it was my second year at the Lesley MFA program where I wondered what life would be like for a young person like me growing up in Iran. Granted Sahar and I are completely different, she’s a lot smarter and has a hot girlfriend in her senior year (I was a scaredy cat and didn’t date in high school).

EK: Your main character, Sahar, is a seventeen-year-old girl who has been born and raised in Iran. Your parents immigrated to the United States from Iran before you were born. I wondered how much of writing Sahar’s story involved imagining how different your life would be if you had been born and raised in Iran?

SF: I think as I was writing the manuscript I wondered a lot if I had any right to write this story as I have been to Iran a handful of times, but will never fully realize what it is to live there. And I am not an authority on everything Iran or everything LGBT there. It is a novel, not a research paper. But there are 76 countries in the world where there is anti-gay legislation and homosexual acts are illegal and punishable. It’s an issue worth exploring and because I am familiar with the cultural mores of Iran, I felt a little more equipped to write a story set there. I don’t think I will ever write another story set there, but I was passionate about this particular story and its subject matter.

EK: Sahar is forced to examine the concepts of gender and sexuality and whether they are independent aspects of her identity. Did you know as you began writing what she would learn? Or did you learn it with her as you wrote her story?

SF: I wanted to make the distinction between gender identity and sexual orientation because I think even people in the West do not understand the distinction nor really want to in some cases. I did know what Sahar’s true identity was and her exploring the idea of gender reassignment surgery was something she saw as her only option. I knew how the story would begin and end, but was surprised where certain characters took me in particular chapters.

EK: If the government and the religious leaders accept transsexuality and even encourage reassignment, but not being homosexual, doesn’t that place some people in the very uncomfortable position of having to choose between their sexuality or their gender?

SF: You have to also understand if you grew up with the idea that homosexuality is a sin and you don’t want to sin but you have certain feelings, I think a lot of young people think this may be a solution. Unfortunately this is not a solution and even though being transsexual is legal, being transgender is discouraged and the transsexual community still face discrimination. The documentary Be Like Others by Tanaz Eshaghian was very helpful to me and I recommend everyone watch it. You can watch it here.

EK: I read that as a teen you tried to find books that spoke to your experience, but that much of the literature about LGBTQ teenagers didn’t really speak to your experience. Did you find any books that spoke to you — even with a queer subtext — in which you felt like you saw yourself? Any more recent favorite LGBTQ books with more diverse characters?

SF: In recent years I love Pretend That You Love Me by Julie Ann Peters, Geography Club by Brent Hartinger, Candy Everybody Wants by Josh Kilmer-Purcell, The Miseducation of Cameron Post by Emily M. Danforth, Ash by Malinda Lo, to name a few. But as a teenager there was Annie On My Mind by Nancy Garden and then if I wanted to read about Eastern characters there was Shabanu: Daughter of the Wind by Suzanne Fisher Staples, so there really wasn’t a whole lot of overlap. But I identified with characters who weren’t like me but that I thought were pretty cool. Especially in comic books/graphic novels. Strangers in Paradise was my jam.

EK: Sahar’s cousin Ali is such an interesting character. And through him Sahar, and the reader, get a glimpse into Iran’s hidden LGBTQ subculture. How did you research the LGBTQ subculture in Iran? Were there aspects of it that you found interesting or of note, but that didn’t make it into the book?

SF: A lot of my research happened stateside because I wasn’t going to compromise anyone’s life for a novel. I read a lot of articles, watched a lot of documentaries, researched a lot about the lives of LGBTQ Iranians who had left Iran and were seeking asylum or were living in the West. There are great organizations like ORAM who help people from all over the world seek refuge. To find out how you can help visit: oraminternational.org. There is another organization in Canada called IRQR which deals with queer Iranian issues headed by a gentleman named Arsham Parsi who is an Iranian activist. You can visit that website here.

And when I went to Iran I was learning a lot about setting, spoke to lots of different people about their day to day lives, spent time in people’s homes religious and secular. But it’s difficult to get specific statistics or ask as direct questions as I would have liked because I didn’t want to compromise anyone. That’s the great thing about fiction, it can be based in truths but ultimately the story you tell is entertaining enough to get people to care about issues.

EK: Is there a body of LGBTQ fiction by Iranian authors or ex-patriots? If so, how is it exchanged or disseminated within Iran?

SF: I can’t speak to that as I don’t live there, but this article about a poet in Iran may explain more. There is also a big e-publishing push for books that are censored in Iran headed by a group called Nogaam. My thing with censorship is that it’s counter intuitive because the more forbidden you make a thing, the more people become curious and want to read/listen/watch whatever is being censored.

EK: What are you working on now?

SF: I have a book that should be coming out summer 2015 from Algonquin Young Readers (who are amazing) about a young Persian-American closeted lesbian in prep school. A lot lighter than If You Could Be Mine and different in a lot of ways.

>>>

E. M. Kokie’s debut YA novel Personal Effects (Candlewick Press, 2012) explores loss, recovery and competing visions of masculinity in the shadow of the conflict in Iraq. It was a YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults and Amazing Audiobooks for Young Adults Top Ten, a Lambda Literary Award Finalist, and a 2013 IRA Young Adult Honor Book. Visit her at www.emkokie.com or on Twitter.

E. M. Kokie’s debut YA novel Personal Effects (Candlewick Press, 2012) explores loss, recovery and competing visions of masculinity in the shadow of the conflict in Iraq. It was a YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults and Amazing Audiobooks for Young Adults Top Ten, a Lambda Literary Award Finalist, and a 2013 IRA Young Adult Honor Book. Visit her at www.emkokie.com or on Twitter.

<<<

Sara Farizan’s If You Could Be Mine is now available. Follow Sara on Twitter.

>>>

Want to win Sara Farizan’s If You Could Be Mine and E.M. Kokie’s Personal Effects? Enter the Giant YA Pride 2013 Giveaway!